Stanislaw Lem

In 1976, in a preface to the classic Russian science fiction novel A Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, the great Theodore Sturgeon mentioned that Stanislaw Lem was then the most widely read science fiction writer in the world. Sturgeon loved to provoke, but he always did so on a factual basis. Ursula K. Le Guin, another internationalist pillar of writing, wrote an introduction to Lem’s Solaris. Testimonials to Lem’s importance may be found from any number of writers. As usual for the US market, however, translated fiction is a steep hill to climb for readers’ acceptance and enthusiasm.

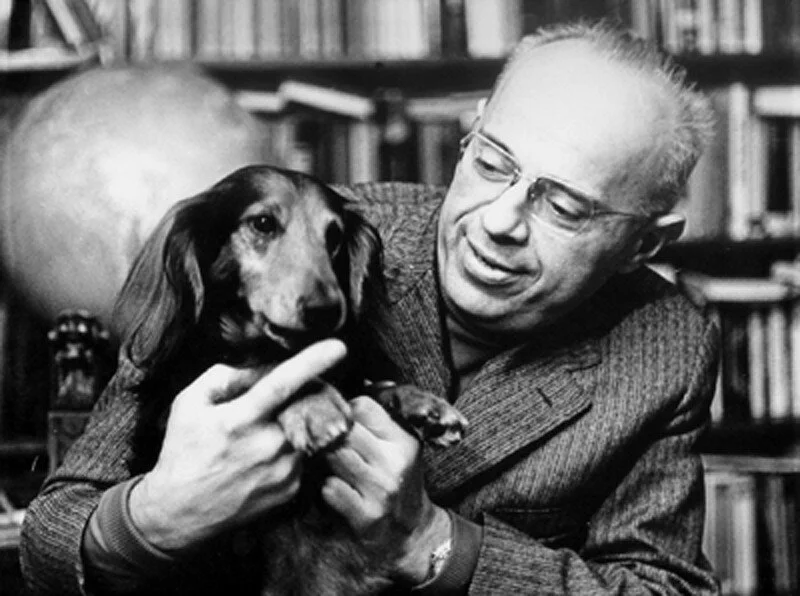

Lem (1921-2006) was a Polish fiction writer and wide-ranging essayist on philosophy and literary criticism. He has been translated into more than 50 languages and sold scores of millions of copies worldwide. He had a talent for the satirical approach to the future, but he also was a skilled investigator of dark psychological depths in what seemed to be straightforward adventure stories. He knew when not to overexplain — indeed, the impossibility of communication was a theme of the work of this Pole born in Lviv, which became part of Ukraine, who trained to be a doctor and could not bear the sight of blood, who wrote star-spanning works of imagination under Soviet censorship guidelines.

Recently, Lem has had the posthumous good fortune to be published by MIT Press. The attractive editions inspired me to create this page dedicated to him. I will be adding the many title of his earlier primary publisher, Harcourt, as I get the opportunity.

Dialogues

Dialogues

The first English translation of a nonfiction work by Stanisław Lem, which was “conceived under the spell of cybernetics” in 1957 and updated in 1971.

In 1957, Stanisław Lem published Dialogues, a book “conceived under the spell of cybernetics,” as he wrote in the preface to the second edition. Mimicking the form of Berkeley’s Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous, Lem’s original dialogue was an attempt to unravel the then-novel field of cybernetics. It was a testimony, Lem wrote later, to “the almost limitless cognitive optimism” he felt upon his discovery of cybernetics. This is the first English translation of Lem’s Dialogues, including the text of the first edition and the later essays added to the second edition in 1971.

For the second edition, Lem chose not to revise the original. Recognizing the naivete of his hopes for cybernetics, he constructed a supplement to the first dialogue, which consists of two critical essays, the first a summary of the evolution of cybernetics, the second a contribution to the cybernetic theory of the “sociopathology of governing,” amending the first edition’s discussion of the pathology of social regulation; and two previously published articles on related topics. From the vantage point of 1971, Lem observes that original book, begun as a search for methods “that would increase our understanding of both the human and nonhuman worlds,” was in the end “an expression of the cognitive curiosity and anxiety of modern thought.”