Stanislaw Lem

In 1976, in a preface to the classic Russian science fiction novel A Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, the great Theodore Sturgeon mentioned that Stanislaw Lem was then the most widely read science fiction writer in the world. Sturgeon loved to provoke, but he always did so on a factual basis. Ursula K. Le Guin, another internationalist pillar of writing, wrote an introduction to Lem’s Solaris. Testimonials to Lem’s importance may be found from any number of writers. As usual for the US market, however, translated fiction is a steep hill to climb for readers’ acceptance and enthusiasm.

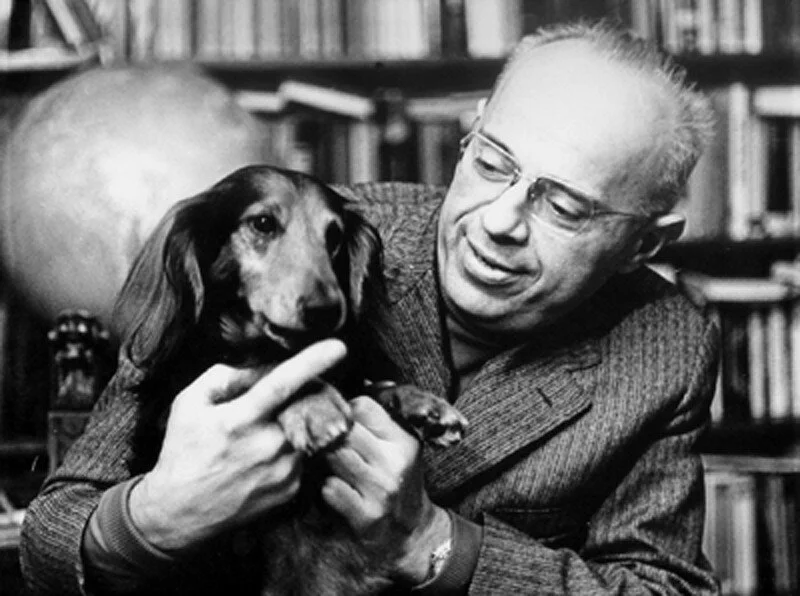

Lem (1921-2006) was a Polish fiction writer and wide-ranging essayist on philosophy and literary criticism. He has been translated into more than 50 languages and sold scores of millions of copies worldwide. He had a talent for the satirical approach to the future, but he also was a skilled investigator of dark psychological depths in what seemed to be straightforward adventure stories. He knew when not to overexplain — indeed, the impossibility of communication was a theme of the work of this Pole born in Lviv, which became part of Ukraine, who trained to be a doctor and could not bear the sight of blood, who wrote star-spanning works of imagination under Soviet censorship guidelines.

Recently, Lem has had the posthumous good fortune to be published by MIT Press. The attractive editions inspired me to create this page dedicated to him. I will be adding the many title of his earlier primary publisher, Harcourt, as I get the opportunity.

Highcastle: A Remembrance

Highcastle: A Remembrance

A playful, witty, reflective memoir of childhood by the science fiction master Stanisław Lem.

With Highcastle, Stanisław Lem offers a memoir of his childhood and youth in prewar Lvov. Reflective, artful, witty, playful—“I was a monster,” he observes ruefully—this lively and charming book describes a youth spent reading voraciously (he was especially interested in medical texts and French novels), smashing toys, eating pastries, and being terrorized by insects. Often lonely, the young Lem believed that he could communicate with household objects—perhaps anticipating the sentient machines in the adult Lem's novels. Lem reveals his younger self to be a dreamer, driven by an unbridled imagination and boundless curiosity.

In the course of his reminiscing, Lem also ponders the nature of memory, innocence, and the imagination. Highcastle (the title refers to a nearby ruin) offers the portrait of a writer in his formative years.